“Sidetracked: Why Our Decisions Get Derailed, and How We Can Stick to the Plan” is the latest book by Francesca Gino, associate professor at Harvard Business School. Exploring and explaining the factors that affect our behaviour, it is the culmination of over ten years of research projects, and offers not only explanations of why our decisions and plans remain unfulfilled, but also how this affects others and how getting sidetracked can be avoided.

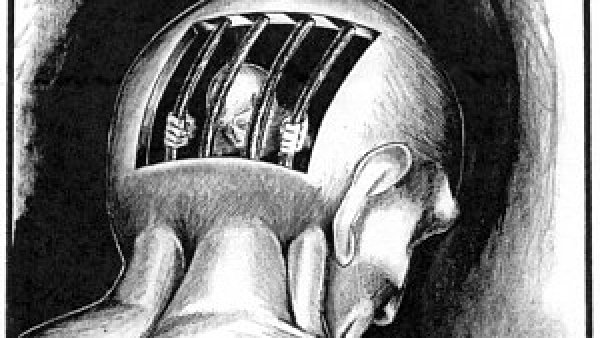

It has happened to all of us; we make plans to study the entire weekend, but find ourselves watching bad reality TV instead. We make plans to go to the gym, but instead we eat a pound of ice-cream. Our decisions, whether important or small, invariably seem to go awry. Gino, who has spent the last ten years researching aspects of human behaviour and decision-making, has emerged with a study of all the factors that cause us to veer off-track.

Gino’s book reveals that our inability to make a decision and stick to it is caused by three main factors; forces from within ourselves, forces from our relationships with others and forces from the outside world.

Forces from within ourselves

Gino identifies forces from within ourselves as being our perception of our own abilities, our emotions and our narrow focus; in short, we are overconfident, emotional and irrational. One of the studies Gino cites in her book is a study where she questioned people about who they thought would go to heaven: themselves, Mother Theresa or Michael Jordan. While Mother Theresa and Michael Jordan got 79% and 65% respectively, 87% of the participants listed themselves.

Gino states that our emotions have a great impact on our decisions, especially when we fail to identify the source of those emotions. The example she uses is arriving to a date angry because you were stuck in traffic. Your emotion will cloud the date and you will conclude that the date was bad, rather than that you were in a bad mood and thus the date only seemed bad.

And how, exactly, are our decisions irrational? According to Gino, and over thirty years of research carried out by economists, our decisions are not a result of logical reasoning but a culmination of circumstance, factors preceding the decisive moment and our environment.

Forces from our relationships with others

Gino’s research has revealed that even the smallest things can affect our view and reasoning and, consequently, our decisions; even the occasion of having the same first name as someone colours our decision-making.

“We tend to look at others in order to evaluate ourselves, and that can get in the way of making good decisions,” says Gino. In this way, we might base our idea of an ideal salary for a job on what others are paid for doing it, or we may choose to act or dress in a certain way because of how our colleagues, friends or peers act or dress.

Another problem getting in the way of our decisions is our inability to place ourselves in other peoples’ shoes: by taking other peoples’ opinions into perspective we are likely to come up with a plan or decision that is more likely to last.

Forces from the outside world

These are what characterize the context in which we make decisions; they include irrelevant information and the environment we are in. ‘Sidetracked’ reveals that even the different phrasing of a question posed to us can have a significant effect on our decisions.

"Thank you" as a motivator

The experiments Gino carried out as part of her research on this topic also uncovered that gratitude and expressing thanks can act as a brilliant motivator in and out of the workplace. Recent experiments have already proven that money is not as effective in motivating people as we think, as we can see in this video, and Gino has stated that by missing chances to express gratitude, organizations and leaders lose relatively cost-free opportunities to motivate.

“I spend a lot of time working inside organizations and see teams working together to accomplish a task, usually with a deadline,” she said. “Oftentimes, you don’t see the leaders going back and actually thanking the team members. Those are situations where expressions of gratitude from leaders could have wonderful effects.”

The experiment she carried out consisted of 57 people who were asked to give feedback on an assignment to Eric, a fictitious student. Half were e-mailed back with thanks – ‘I received your feedback on my cover letter. Thank you so much! I am really grateful’ – the other half only received acknowledgement – ‘I received your feedback on my cover letter.’

The participants were then contacted by Steven, another fictitious student, asking for feedback on his assignment. 66% of the people in the group that had been thanked by Eric agreed to help him, compared to only 32% in the other group.

According to Gino, this was the most surprising outcome of her research.

Bottom line: Do you think that being informed on why our decisions fail and why we veer off track will help us avoid this in the future? And will you be using ‘thank you’ to motivate?

Přidejte si Hospodářské noviny

mezi své oblíbené tituly

na Google zprávách.

Přidejte si Hospodářské noviny

mezi své oblíbené tituly

na Google zprávách.

Tento článek máteje zdarma. Když si předplatíte HN, budete moci číst všechny naše články nejen na vašem aktuálním připojení. Vaše předplatné brzy skončí. Předplaťte si HN a můžete i nadále číst všechny naše články. Nyní první 2 měsíce jen za 40 Kč.

- Veškerý obsah HN.cz

- Možnost kdykoliv zrušit

- Odemykejte obsah pro přátele

- Ukládejte si články na později

- Všechny články v audioverzi + playlist